In the half century since Bowdoin College stepped up its commitment to diversifying its academic and cultural landscape, the face of Bowdoin has changed.

Asian, African American, Latino, Hispanic and Native American students now account for over thirty percent of the student body. Academic departments include over 20 percent faculty of color.

The numbers tell a story, an important one, about the collective will of the entire College community to transform Bowdoin to more deeply reflect the world at large. But there’s another way to understand how diversity has taken root at Bowdoin. Take a look through the course catalogue.

Some classes virtually sizzle off the page: Black Women, Politics, and the Divine; Comparative Slavery and Emancipation; The Archaeology of Gender and Ethnicity; Staging Blackness; Christianity and Islam in West Africa; He Loved Us Madly: Duke Ellington; French Caribbean Intellectual Thought; White Negroes.

These are all courses being offered by professors in Bowdoin’s Africana Studies program, which is fast becoming a major crossroads for some of the most innovative cross-disciplinary teaching and research taking place at the College.

Bowdoin’s Afro-American Studies program began, as did most in the late 1960s, in the red-hot center of the civil rights movement. Students and faculty across the country pressed institutions to establish academic programs committed to black studies. They fought to pry open a largely Eurocentric curriculum to include the contributions of Africans and African Americans to discussions of history, economics, politics and society.

Initially, courses focused on the United States. As the number of contributing faculty members swelled, the program included a wider range of historical, political and literary exploration. Lynn Bolles, an anthropologist who researched Jamaica, headed up the program through much of the 1980s and brought a more international focus to the curriculum.

Historian Randy Stakeman took over the reins in 1989, ostensibly for a three-year turn, and ended up heading the department for much longer than he bargained, 17 years. He pushed to expand and codify the global focus of the program, which eventually led to the 1993 name change to Africana Studies.

“It was obvious even then that there was globalization going on in a way that would bring people of color from non-U.S. roots into the country and that needed to be studied,” said Stakeman. “You needed to look at Africana Studies in the same way that you looked at Asian Studies: the examination of a large contingent of the world. Once you expand your focus, rather than thinking of it as a sop or something you were throwing out to the African American students, it changes your entire conception of what it should be.”

By the time the program celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2009, Africana Studies at Bowdoin looked a whole lot different than when it started.

For one thing, the program itself has moved from cramped quarters in the Russwurm Center to airy, new digs in Adams Hall. Faculty offices, seminar rooms and classrooms are spread across two floors.

Extra-curricular programming is sprawling too: Africana Studies partners broadly with other departments to bring internationally known scholars and artists to campus. The 2010 lineup included a visit by Irvin Mayfield and the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, a talk by trailblazing activist Angela Davis — and a performance by D’lo, who bills himself as a transgender, queer, Tamil Sri-Lankan, political, hip hop theatre artist.

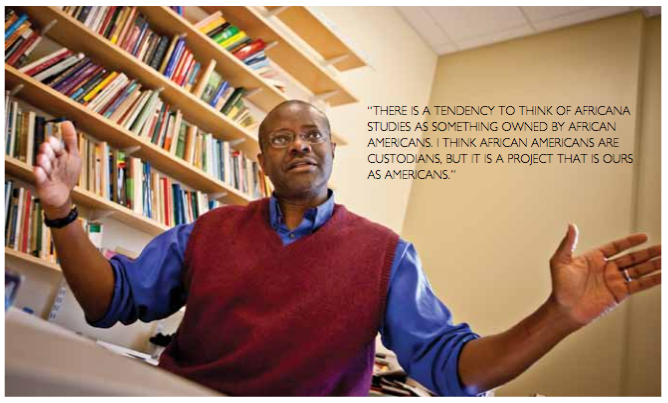

The program, says its director, Geoffrey Canada Professor of Africana Studies and History Olufemi “Femi” Vaughan, is setting a feast that is not only succor for students of color, but is at the heart of the College’s deepest multidisciplinary exploration of what it means to be American.

“There is a tendency to think of Africana Studies as something owned by African Americans,” says Vaughan, who came to Bowdoin from Stony Brook University in 2008. “I think African Americans are custodians, but it is a project that is ours as Americans.

“There’s no way you can understand America without putting black experience at the center of its citizenship, economy, history, music, art, science. It’s not marginal. It’s essential to the American experience and it engages the wider world. We want to see blackness as something that is evolving, that is tied to a tapestry that is national and global. It is not limited to one place at one time. Black has multiple meanings.”

“Africana Studies has this opportunity to do things which aren’t being done anywhere else in the academy now,” agrees Randy Stakeman. “Because it is not confined by the boundaries of any one discipline, you can look at new things, or look at old things in new ways. It’s not necessary to do basic history or English courses — there are other departments for that.”

Invigorating Africana Studies

The program’s new vitality is the result of a concerted effort to put Bowdoin’s Africana Studies program out front nationally as pipeline for new scholarship, teaching and civic engagement — even as some institutions are downsizing or blending African American studies into other programs, such as history or multicultural studies.

Four years ago, Bowdoin hosted a forum on the state of the field, which brought experts from around the country to Bowdoin to consider how the discipline had developed and where it might be headed.

“What we discovered was a discipline uniquely suited to bridge the traditional divisions of the humanities and social sciences,” notes Dean for Academic Affairs Cristle Collins Judd. “The field of Africana Studies connects scholars, researchers and artists to some of the most pressing political, social and environmental issues of our times. We felt that Bowdoin could build on the multidisciplinary strength of our existing program while carving out an important niche for new scholars and new scholarship.”

Femi Vaughan took over the helm of Bowdoin’s program in 2008, after having spent nearly 20 years developing programs at Stony Brook in various capacities, including Associate Dean of the Graduate School, Interim Chair of Africana Studies, and most recently, as Director of the College of Global Studies and Associate Provost.

Vaughan is an internationally recognized scholar of modern African political and social history whose interdisciplinary examinations of modern African state formation have earned him widespread recognition in the field. His prize-winning book, Nigerian Chiefs: Traditional Power in Modern Politics, 1890s-1990 (2000, Univ. of Rochester Press), is considered a seminal study in modern African political history.

Vaughan’s is a mind of connection making. It isn’t uncommon to hear Femi begin a discussion on one topic — say, the formation of the modern African state — and end up talking about economic issues of urban Latino and Hispanic communities in the U.S. Possibly, by way of globalization trends, pinpointing gender and development issues in Nigeria.

These aren’t random rabbit holes — rather, they are part of his formidable reach as a political scientist who seems to hold the modern history of at least three continents in his hands at once.

Vaughan’s rapacious intellect is enwrapped in a sweet, almost courtly, means of address that has the knack of making people feel they are also brilliant simply by conversing with him. “Your question is exactly right,” he will say to a new student or colleague, adding: “But of course this raises another question as well…” And he’s off.

Although Vaughan’s passionate commitment to inclusivity may account for part of the program’s new vigor, a generous infusion of support from the recently completed capital campaign didn’t hurt either.

Along with Vaughan’s appointment, there are three new tenured or tenure-track faculty hires dedicated to Africana Studies, bringing the total number of direct and contributing faculty members to 15. They span disciplines from slave literature to jazz, African archaeology to Francophone literature, abolitionism to modern African political and social history.

Among the dedicated faculty lines, Assistant Professor of Africana Studies Tess Chakkalakal is a specialist in 19th century African American literature and culture, with expertise in the works of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Assistant Professor of Africana Studies Judith Casselberry, an anthropologist who explores intersections of religion, music and gender.

The program’s newest hire, Brian Purnell, who began teaching in Fall 2010, is a historian of post-WWII African American urban life with special focus on the civil rights and Black Power movements, modern liberalism and the development of the U.S. “urban crisis.”

“There definitely is a buzz on campus,” says Africana Studies/French major Awa Diaw ’11. “There were maybe two professors in that department in my sophomore year. Seeing the number now, I’m amazed. They are really stepping up their game, adding a wide range of courses to choose from. Some schools don’t even have Africana Studies programs,” she observes. “Seeing this in a place like Maine is amazing.”

A Commitment to Mentoring

Although it’s certainly not the mission of the Africana Studies program to function as an academic or social gateway for students of color at Bowdoin, it’s part of the reality. Mentoring students can be a fairly intensive part of the package for faculty, acknowledges Vaughan.

“If you are connected with Africana Studies you’d better know that mentoring students from diverse populations such as Asian, Black, Latino is central to what you are,” says Vaughan emphatically. “It’s not antithetical to your scholarship and research. You are driven by the subject of race and racism. The personal is the professional. It’s the problem that you want that academic field to help you to resolve.

“One of the most central parts of your identity as a scholar is to engage those questions and challenges as they unfold. Even when they unfold in your office.”

Ad hoc (and actual) academic advising takes place in departments all around campus; it’s not just reserved for Adams Hall, but because there is a concentration of faculty of color in Africana Studies minority students at Bowdoin sometimes feel more comfortable seeking out professors there — particularly in the early stages of their college career before they have been exposed to a wide range of professors and pathways.

“Building and supporting an intellectual environment for all of our faculty and all of our students is an essential part of the mission of the College,” observes Bowdoin President Barry Mills.

“Africana Studies is a genuine academic discipline that stands on its own, and one that also offers important interdisciplinary opportunities for students and faculty alike. It is also a program that attracts impressive scholars to Bowdoin—scholars who can help us advance the discipline and who can and do serve as role models and mentors for our students. To be able to say to these students, ‘You can model your career after Judith Casselberry or Tess [Chakkalakal],’ that is a wonderful and valuable collateral benefit. For all of these reasons, we are stepping up our commitment to this pure academic discipline.”

Creating a Bold, Global Vision

Indeed, putting the academic discipline at the forefront is one of the greatest challenges Vaughan has faced in his tenure at the College. It was no small endeavor to convene discussions with longstanding, contributing faculty members and new core faculty alike to carve out a vision for the program that embraces its deeply multidisciplinary nature while defining an essential scope.

Eventually, those talks led to a completely new major/minor curriculum, which became active in Fall 2010. It now allows students to hone in on either an African American focus, or concentrate on African and African Diasporic studies. Core courses will include a plateful of both.

“Can you major in Africana Studies if you are preoccupied with African American issues and know nothing about Africa?” asks Vaughan. “We are saying no. You have to understand the development of African states, colonization, how African nations have responded to Western forces. Likewise, any discussion of African American issues must touch on some aspect of African or Diaspora history.”

Within those wide bookends, however, is a lot of room for invention in a field that is still inventing itself. The abiding modus operandi of Africana Studies is to look at old things with new eyes, to make connections, to incorporate the personal into the scholarly. It’s part of the literary tradition of the African/African-American experience, much of which was transmitted orally, musically, or through personal diary or account prior to the 20th century.

That may also account for the originality of many courses being developed here and at other progressive Africana Studies programs.

Judith Casselberry’s course Black Women, Politics, Music and the Divine incorporates anthropology, ethnomusicology, literature, history and performance to view ways that black women have expressed their identities through artistic production, especially through song.

Seated beside the sleek controls of a multimedia console in a techno-fitted classroom in Adams Hall, Casselberry regularly launches videos and soundtracks of some of the greatest black singer-songwriters of the day — Grace Jones writhing in controlled power and pain; gospel great Shirley Caesar lifting it up; Nina Simone’s haunting rendition of “I Loves You Porgy.”

“Usually we focus on something like the history of slavery and how black people built themselves up,” noted Africana Studies major Tranise Foster ’11, who took the course in Fall 2009. “But in this course we were listening to the music and dissecting it, going behind it, talking about the use of music as therapy and expression, finding out what the ideology is. It was very revealing to me. It allowed me to see myself in a different way. As a black woman… you’re always conscious of the past.”

“In coming together with students it’s important to me that they keep themselves really open to understanding that social identity, how we make ourselves, is fluid,” says Casselberry. “So-called “legitimate” knowledge doesn’t always come from the necessarily expected spaces.”

Casselberry should know. Her trajectory into the world of academia was hardly traditional: From 1984 to 1994, she was part of the famed folk duo Casselberry-DuPree — a leading voice and presence for women of color in the women’s movement. She continues to perform as a singer with Toshi Reagon and BigLovely.

“I operated in a world of performance where social justice was primary and issues of spirituality were central to what I was doing,” recalls Casselberry. “My masters and doctoral work allowed me to legitimize my observations and life experience within a theoretical framework. To be able to grapple with these things in a broader sense, to make distinctions between race and racism, and gender and sexism, it gave me a new way to approach my life.

“But it certainly wasn’t without its challenges to make that transition from being a professional musician to going into the academy,” she adds with a wry smile.

Interestingly, at Bowdoin, and even more widely in the discipline, African American, Africana and Diaspora studies are drawing students (and scholars) from broad backgrounds, notes Vaughan.

Africana Studies/History major Elizabeth Stevenson ’10 said she “just fell into” the major through her curricular explorations. “The first two years at Bowdoin I just took classes that looked interesting to me: The History of Jazz, Africa and the Atlantic World, Race and Ethnicity. These encouraged me to put aside the way I would normally approach some things and see the world. African history has encouraged me to be more open-minded — that sounds so cliché, but it’s true — it has challenged me to understand a totally different world, or cultural, or even a historical viewpoint than I’m used to.”

Many more students take classes, or minor, in Africana Studies than become majors in the field, which is fine by Vaughan. The point, he says, is not to steer students in any direction, but to function as a stepping off place for exploration of issues that sometimes connect in surprising ways.

Judging by the titles of several recent honors and independent studies projects, Africana Studies is breeding some highly original student scholarship: Awa Diaw did a project looking at Muslim women and social change in modern Senegal; Yonatan Shemesh ’08 wrote an honors project titled, “The Integration of Ethiopian Jewish Migrants into Israeli Society; Dennis Burke ’08 examined “Popular Music in the Civil Rights Era.”

Africana Studies is also a place where new and emerging scholars can cut their teeth, as witnessed by a steady influx of scholars coming from the Consortium for Faculty Diversity (CFD). Bowdoin is one of more than 50 colleges and universities who are part of CFD, a program designed to support pre- and post-doctoral scholars from a range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds in pursing teaching and scholarship at liberal arts colleges around the country.

On the student side, the College’s participation in the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship program catches bright minority scholars during their undergraduate years at Bowdoin, providing support for research and encouraging them to go on to doctoral programs in the humanities, social and natural sciences. The first class graduated in 1994 and since then, roughly 74 students have been awarded fellowships, and several of them are now PhDs.

What is Race?

Inevitably, one of the key questions underscoring many discussions in Africana Studies courses is the issue of race.

Inevitably, one of the key questions underscoring many discussions in Africana Studies courses is the issue of race.

“What is race?” asks Tess Chakkalakal, who throws her hands wide, as open as the question itself. “Does it exist or is it a socially constructed fiction? If we do want to move beyond race, how do we do it? What would that world look like? Would it be a good world?”

“Too often, we pussy-foot around this question, but in Africana Studies we get to confront the issues head-on, without having to be so careful. I think that kind of conversation is necessary, but it’s only a starting point for many other conversations.”

Vaughan agrees that the issue of race is central to Africana Studies, but cautions that it must be neither the sole domain of the discipline nor the sole focus of the discussion.

“It doesn’t serve the field of study well, and it doesn’t serve our nation well, when a subject matter is reduced to one thing, however important that one thing may be,” says Vaughan. “Yes, it’s true there is the crucible of race that is essential in the American experience, but we don’t want to reduce people who happen to be of African decent to one essential. It doesn’t belong to one people, one racialized body.”

One place where students can construct, deconstruct — or simply just converse — about race is in Roy Partridge’s Racism course, which he has taught since coming to Bowdoin in 1994.

“What I hear time and again is that students don’t talk about race much outside of their classroom,” says Partridge. “This is one of the places where it’s encouraged but you can do so in some safety without having to worry about making grievous political mistakes, about not being PC in your comments.

“I think people regularly stumble on new awarenesses of each other through making mistakes, whether they’re white or black, Asians or Latinos,” adds Partridge. “In virtually every class I have there is some new understanding between people across racial lines, and beyond assumptions about class, ethnicity and gender.”

This is markedly observable at a time when America — and Bowdoin — is being reconfigured by an influx of people from Asian, African, Caribbean, and Latin nations. Awa Diaw, who is a native of Senegal, said she felt disoriented by consideration of herself as a raced individual when she got to the States.

“Coming from Senegal we don’t talk about race,” says Diaw. “There is no such thing as race. But coming to the U.S., race is visible, it’s a big thing.”

Diaw says she has come to understand more about the differing experiences of people of African descent around the world as she has studied more deeply in the field. She says she can observe the framework of racism that is embedded into the American experience, but finds the discussion soon bleeds over into other areas without a clear ethnic or racial definition — issues of class, culture, and political and economic oppression that are common to many disenfranchised groups.

“I feel like all the issues end up coming into play, in a way they all connect,” says Diaw. “I mean, Africana Studies has a program — there’s also Latin American Studies, Asian Studies. They are all minorities in a sense, but they find some form of connection. I feel like they are all related one way or another.”

“Many of the issues pertaining to African American studies also pertain to Asian, Asian-American, Latino, and Hispanic studies,” agrees Vaughan. “To the degree that questions pertaining to the black experience help us think about the problems of inequality, social justice, educational disparity, politics, class, gender, Africana Studies is very much connected to other disciplines. They bounce off each other, they relate and confirm, and sometimes it’s a relationship of ambivalence. That’s okay.”

Building The Beloved Community

In spite of shrinking national support for humanities programs in higher education, interest in the field of Africana, African-American and Diaspora studies appears to be on the rise.

There has been a marked increase in applications to long-established programs at institutions such as UMass-Amherst (widely considered to be a locus of scholarship in the discipline) and master’s programs at prestigious colleges such as Brown University are expanding to offer doctoral degrees.

And it’s not just scholars of African descent entering the field

Former Mellon Mays Scholar Tony Perry ’09, who is in the first stages of what he hopes will be a Ph.D. in African American political and social thought, spent a year applying to graduate schools before being accepted into a prestigious program at Purdue University. He found himself competing with a large percentage of non-minority candidates for graduate school slots, which may be a growing trend in the discipline.

“There’s a lot of exciting scholarship coming out of the field recently — issues about race, politics, sexual identity, class, globalism, third world economy,” says Perry. “A lot of people want to move in that wave or momentum. It is exciting not only for black people.”

He is thoughtful a moment, then adds: “I think it’s good for the field, but it also gets complicated because historically it has sometimes been problematic when you don’t have people in a given community reading and writing their own histories. Things can get skewed.

“But in my mind, for this to work, there will have to be cooperation, dialogue in which views and perspectives from a range of people can be included to further the field. It will be very interesting to see what develops.”

Perry has hit on the very thing that lights Femi Vaughan up incandescently.

“This is what Dr. King talked about when he spoke of the ‘beloved community,’ “ says Vaughan. “In these dialogues we can have together, in this enterprise of teaching and learning that takes place throughout the Bowdoin community, we can look beyond ethnicity, gender, sexuality, nationality, and say, ‘We all belong and in order for me to do well, my fellow man must do well.

“We can ask those questions not as activists, but as researchers and scholars. We can put those questions front and center in a community of common good and common will.”

All photos by Brian Wedge.

Article originally appeared in Bowdoin Magazine, March, 2011.