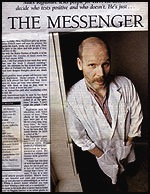

Every workday, Miles Rightmire gets up, drinks some French roast and says his prayers. He packs his lunch, works out at the gym. Then he goes to the office and tells people if they will live or die.

Every workday, Miles Rightmire gets up, drinks some French roast and says his prayers. He packs his lunch, works out at the gym. Then he goes to the office and tells people if they will live or die.

A counselor with the Maine Bureau of Health, it is his job to give people the results of their tests for HIV.

“At one point, I told four people in one week they were positive. That was the week I stopped counting,” says Rightmire. He estimates he has tested some 5,000 people in his office at Portland City Hall. In the process, he has learned their deepest thoughts about sex, death and survival.

“When they’re positive, some people will become very angry,” says Rightmire. “Some people, if they’re parents, will talk about the fact that they have children. Some cry. Some get very, very rational.

“I just stay with them as long as they want to connect with me. I kind of know the path.”

Rightmire, 44, learned the path after weathering a few bends in his own life.

As an openly homosexual man, he says he has faced the issues with which many of his clients struggle. “I’ve looked at all my questions,” he says. “I don’t judge the people I talk to.”

Rightmire says he identifies with their sense of loss. “The effects of the disease have been part of my life for a long, long, long, long time,” he says. “Very important people in my life have died. My oldest friends. So AIDS is a fact of life.”

It’s Rightmire’s gentleness, not his directness, which disarms. His face is a moon of smooth surfaces, dominated by large, quizzical eyes. He speaks in a whisper and listens with graceful attention.

“I think that this kind of work has been a good place for me to pull out a lot of nurturing energy that I have,” he says. “I live in a very human world where people matter. Where their joy and pleasure is acknowledged, as well as their pain. Where it doesn’t matter whether you walk through the door wearing a $600 suit or a sweatshirt.”

Rightmire came to his work after a career that included sever years as an English teacher in an urban ghetto in Ohio.

A native of Chicago, he moved to Maine in 1981. It was the kind of place, he says, where he knew he could live “without a television, a microwave, a CD player.”

He worked variously as a manager for Portland’s Good Day Market, a health-food cooperative, and as a sex-education teacher and child-care worker at the Sweetser Children’s Home in Saco.

After organizing risk-reduction education for gay men in Maine, the HIV counseling job came open and Rightmire went for it. “It’s a wonderful opportunity for teaching willing students,” he says.

His supervisor at the Maine Bureau of Health, Dawne Rekas, said she was impressed by Rightmire’s ability to be very gentle and compassionate and supportive while at the same time appropriately confronting people with their behaviors they don’t want to look at.”

The greatest risk behaviors he hears about, says Rightmire, are unprotected sex and intravenous drug use. Some people who continue risky behavior return many times a year for testing. “There’s a lot of denial around risk,” he sighs.

Although he knows their most intimate secrets, Rightmire doesn’t know the names of his clients. His is one of the sites in the state providing anonymous HIV tests. Last year, 5,557 Mainers met with nearly two dozen counselors like Rightmire. Eighty-three learned what Rightmire describes as “the worst news they could ever hear.”

But, for Rightmire, there are worse things than hearing a positive antibody status. The pain of living, he says, sometimes weighs heavier than the fear of dying. “It’s just devastating to hear a young girl come in who’s been raped,” he says. “Emotionally, for me, that’s a hard 45 minutes.”

During the course of the pre-test counseling session, many people unburden themselves of festering secrets. “Sometimes it’s a relief to have an opportunity to talk,” he says. “I listen very closely. We’re not doing therapy, but we have an opportunity to poke around and see if there’s other trouble too. I want to give them the support and referrals I can in terms of that person’s whole health.”

He has heard tales of sexual abuse, of drug addition, of childhood trauma. “Occasionally people might shock me, but generally I’m not too flappable,” he says. “The plumbing only works certain ways, so there’s not that much different that people do.”

Rightmire seems surprised more by ignorance than by sexual promiscuity.

“Children don’t grow up learning the names of their body parts, so there’s this taboo and bizarre kind of approach to talking about sex. Most people don’t have an opportunity to ask the questions they want to ask. Sometimes people have had confusions about basic anatomy.”

One adult woman, he recalls, didn’t know what her uterus was.

All kinds

The mechanics of an HIV antibody test are simple. Rightmire administers a blood test that takes less than a minute. Then he talks to people about HIV, high-risk behaviors and safe-sex methods.

Although over half of Mainers who have tested positive for HIV are homosexual men, Rightmire says his clients are diverse.

“I see everybody. Maybe you’re going to be sitting with a woman who’s been married for 25 years and her marriage is ending. Maybe you’re sitting with someone who’s just about to take a wonderful trip to China and they need it for a visa. Or maybe you’re talking with the sweetest 70-year-old grandmother who’s going to Florida and needs the test for her dialysis.

“But one thing I’ve learned in this job is how much shame people have about sexuality. Sometimes they have judged themselves very harshly about their sexual behavior and their relationships. They make statements about themselves as they discuss their histories: ‘You must think I’m a real slut,’ that kind of thing.

“This job has smashed some mythologies I had,” he adds, swiveling in his office chair. “The extent of IV drug use, for instance. Anybody might be doing that.

“The stereotype of being the scary, deranged, violent person, that’s what people think of. That’s not my experience. My experience is of people, decent people who have a chemical dependency, people often in trouble in their lives.”

Two percent

Ten days after clients first meet with Rightmire, the HIV antibody test results come back from the lab. Clients are called back to his office to discuss the results. The first thing Rightmire tells them is their antibody status. Ninety-eight percent of the time, he says, he begins with the words: “Good news.”

“Then they sigh or say ‘Yahoo!’ I’ve had people tell me if I wasn’t so ugly, they’d kiss me,” he laughs.

But there are days when he dreads his follow-up meeting. “It’s not a good feeling when you get a positive result,” says Rightmire. “It’s like, uh oh, here it is.”

The first thing he does is make sure the client’s identification number matches the one on the positive test result. Then he takes the person into a small examining room.

“I look them in the eye and explain the result came back positive,” he says quietly. “Then I let them make the next move. Let them ask whatever questions they have, or if they need a private time, I give them that. I need to make sure they don’t feel I’m going to roll over them.

Originally published in the Maine Sunday Telegram.

“I think it takes people a long time for their feet to hit the ground again after collection information like that,” he says. “Many people who tested positive will say that beyond hearing those words, they don’t remember much else.”

When they’re ready, Rightmire sets up HIV-positive clients with a case manager who can help them plan medical and social services. He also tries to offer a ray of hope, describing the motivating force HIV has been in many peoples’ lives.

“HIV won’t stop people from growing, from learning, it won’t stop them from loving.” These are words he has said often, and he rattles them off almost like an incantation. “It’s also very important that it’s not the end of the world.”

He catches himself on this one. “Well, every world will end eventually. But I know many who are HIV positive who are leading full, rich lives. The average a symptomatic time a person has who is HIV positive is about 10 years.”

Spreading the word

One of the most delicate tasks of Rightmire’s job is partner notification. Rightmire will contact clients’ past or present sexual partners to inform them that someone they have slept with – who wishes to remain anonymous – has HIV.

“It’s almost always done face to face, in as quiet and private and non-intrusive a way as we can manage,” he says. That may mean meeting them when they get home from work, or catching them at their car.

“I might knock on their front door and say, ‘Hello, my name is Miles. I’m a counselor with the Bureau of Health. Do you have a couple of minutes to talk about something important?”

“People think that’s worse than doing testing, to actually knock on doors and tell people they’ve been exposed to HIV,” says Dawne Rekas. “Oddly enough, that’s been very rewarding. We find a lot of clients who are really in need, who value having this information; it often serves a catalyst for changing their behavior. It really is an emotional time for people.”

Equally challenge is working with families of clients with AIDS. “Often, the family is freaked out,” says Rightmire. “They don’t understand disease transmission and become concerned about things like doing the laundry, or is it OK to use the same plates? Families need reassurance and information on basic precautions.”

He looks out his window as police sirens screech up Congress Street.

“Whatever a person’s antibody status is, the only thing the test will change is what they know. What an HIV antibody test counselor does is to take a little journey with somebody from a place of not knowing to knowing.”

Published in Maine Sunday Telegram