“The project came to me,” says Shu-chin Tsui, her eyes gleaming. She carries a large stack of oversized art catalogs, treasured artifacts from a recent trip to China.

Tsui clutches the books as if they were contraband. And maybe they are.

Two summers ago, the Bowdoin College Associate Professor of Asian Studies was in Beijing where she was exposed to an exhibition of experimental works by contemporary women artists. Intrigued, Tsui purchased the exhibition catalog and other art albums and shipped them home.

When she opened the box in Brunswick, the catalog and art books had disappeared. “This collection must have been confiscated by customs,” laments Tsui. “The first summer research is gone.”

That wasn’t the only thing missing. As Tsui began to research women artists in contemporary China she discovered that, while they have been an active presence in art scenes worldwide, there has yet to be a book-length study of the subject in English.

“One encounters their works in galleries, museum exhibitions, and auction houses,” says Tsui. “Nonetheless, women’s art as discursive subject and innovative practice is absent from critical discussions and academic publications. Why is there nothing on women artists?”

Tsui has now begun working on what she hopes will be a groundbreaking book about the subject. “That idea is in my mind and heart since 2008,” says Tsui, an expert on Chinese cinema and cultural studies. “I feel it is so significant to fill in the literature.”

But where to begin? With only scant published analysis and a few exhibition catalogs, Tsui realized she would have to seek out the artists themselves. A Bowdoin faculty research grant allowed Tsui to return to China this summer, where she made a labyrinthine quest for the sometimes hidden artists.

“I have no idea where I’m going to end when I go there,” she says. “I have a chapter outline, my ideas are clear, but I need to collect materials, get to know artists, and have access to galleries.”

Every day for a month, Tsui hopped into subway cars or taxies to scour Hong Kong, Shanghai and the outskirts of Beijing for art studios and artists. Through a round-robin of referrals, she interviewed more than two dozen artists, critics and curators.

“Every single one, their works and personality are different,” notes Tsui. “Sometimes, they reject you, sometimes it’s a wonderful conversation. That is the adventure.

“I started my journey without knowing anyone in the art circle but ended with more names added to the interview list and a roundtable discussion at Gao Minglu Contemporary Art Center.”

Just weeks after returning, Tsui has turned research into writing. She is focusing on 20 experimental women artists and their works—some well known, others who are without formal training, including one painter who is a migrant worker.

“The writing project will examine how women artists use the female body as a subject and medium to generate an art canon that is gender specific and feminine in rhetoric,” says Tsui.

She turns the pages of one catalog revealing a compelling, disturbing, image: On a drop cloth there is a grotesque heap of sculpted newborn babies, by Beijing artist Jiang Jie. Tsui says it references the

, a grueling 8,000-mile trek over several mountain ranges by roughly 200,000 Red Army soldiers (and women).

“No one talks about how many women lost their lives and babies on their participation in the march,” notes Tsui, adding: “One sees heroic male marchers from revolutionary history books but not women giving birth and giving away their babies as they had to do. I tell Jiang Jie, ‘Your work is shocking but irresistible.’ ”

“When I do this, it’s not just manuscripts I’m writing about,” adds Tsui. “Our bodies are very much connected to the arts. That’s the significance of women’s art. See how rich it is?”

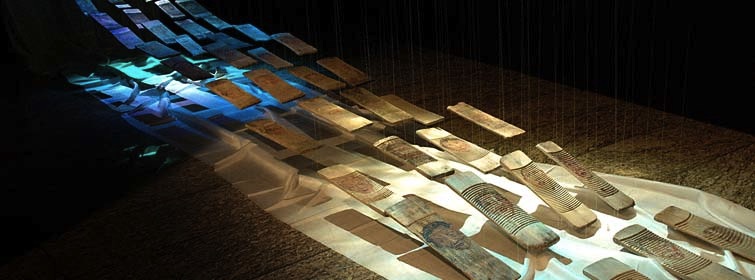

She opens another book, revealing a subtle, beautiful work by artist Tao Aimin, who spent years going to rural villages gathering up old family washboards. She collected over 1,000 pieces, which she exhibited in 2005 in the form of a “River of Women.”

Tsui translates from Tao Aimin’s Book of Women that accompanied the show: “‘What is women’s history?” the artist explains. “Old granny spent her whole life washing and her body is confined in domestic space. Turning the washing boards into installation, I insert the female body into history.’”

This isn’t the first time Tsui has brought a cutting edge study of contemporary Chinese culture into the academy —and the Bowdoin classroom. Her 2003 book, Women Through the Lens: Gender and Nation in a Century of Chinese Cinema, was among the first scholarly examinations of modern Chinese cinema and continues to spur independent studies among students.

Eventually, she says, she hopes to develop a Bowdoin course based on her exploration of experimental Chinese art. “The classroom, for me”, says Tsui, “is a platform where I connect our students to contemporary China. These works of art are so powerful, they draw my eyes and my heart.”

Originally posted on Bowdoin College Web site, Aug. 13, 2010