What do you do when a living legend such as Edward Albee crosses your path? If you are director and theater professor Davis Robinson, you hold your umbrella over his head, and in the time it takes to walk across Bowdoin’s rainy campus, quietly ask America’s greatest living playwright about the earliest influences on his work and life.

What do you do when a living legend such as Edward Albee crosses your path? If you are director and theater professor Davis Robinson, you hold your umbrella over his head, and in the time it takes to walk across Bowdoin’s rainy campus, quietly ask America’s greatest living playwright about the earliest influences on his work and life.

If you are one of the 400 or so people who crowded into Pickard Theater to hear him speak, you drink in Albee’s humorous and sometimes piercing reflections on art, theater, and education, accrued over 80 years of living and writing some of the most treasured plays of the 20th century canon, including Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, The Zoo Story, and A Delicate Balance.

If you are two, senior theater majors, however, you do something a little more personal: You offer up your own works-in-progress for feedback from the master.

Caitlin Hylan ’09, who is directing one of Albee’s more recent works, The Play About the Baby, for Masque and Gown this semester, was among a group of about 30 theater/dance students who met privately with the Pulitzer-prize winning playwright, following his Sept. 26, 2008, Common Hour talk.

“I’ve got things I’m dying to ask him,” she said the day before his visit. “One of the things I’m interested in is how his personal biography has influenced the play. I’m wondering about a possible vaudeville aspect, since his grandfather owned a chain of vaudeville theaters. I’m thinking about toying with a vaudevillian, or clown, element with some of the characters in The Play About the Baby but I don’t want to add anything to the text that isn’t there.”

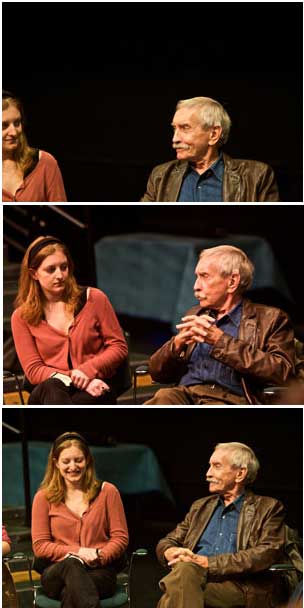

When her big moment came, Hylan sat next to Albee and was able to ask the question herself.

“I did a lot of research about the play before I started,” she began, taking a deep breath. “A lot of reviews talked about the vaudevillian elements …”

Before her question was quite formulated, Albee surprised her with a quick, direct answer that she later said both encouraged and challenged her:

“Why would you tamper with your individuality and creativity by reading that stuff?” he scoffed. “You’re directing the play, don’t pay too much attention to what other people say. It’s not useful; it’s mostly wrong. It’s yourrelationship to the work.”

Albee’s sharp dialectic exchanges kept students and theater/dance faculty spellbound for over an hour, as he described his approaches to character, dialogue, plot, and stage direction—right down to the semicolon and comma. (“Punctuate as if you were composing,” he said. “A semicolon is a longer pause than a comma, for instance.”)

No one was perhaps more attuned to Albee’s presence and comments than was Katharine “Kat” Sherman ’09. Just an hour before, the English/theater major had been informed that Albee would use half the time to give her public feedback on her play, a process known among writers as “workshopping.”

Davis Robinson had forwarded a copy of the promising script-in-progress to the playwright earlier—and Albee had taken the trouble to read it not once, but twice.

“You know that feeling when your stomach falls out and sort of crash lands?” Sherman said, “That was me. It was, oh no, really? I was incredibly nervous.”

While the budding playwright had spent last summer workshopping her writing at the prestigious Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut, direct feedback from the likes of Edward Albee “was huge for me, it was huge,” she said.

Midway through the hour, Albee tuned his attention to her like a bolt of lightning. He emphasized how all plays are based in reality and that all characters must be created as three-dimensional human beings. “They can’t be stick figures, ideas, metaphors,” he said, suddenly turning to face Sherman with a slight smile. “Which is the only problem I have with your play.”

She quietly froze.

“I’ve thought about your play,” he said. “The character of Endymion, does he think he is a shepard? Does the woman think that she’s the goddess of the moon?”

“Well …” she faltered.

“Answer my question. Do you think so? You made her.”

“She is,” said Sherman, regaining her voice. “She wants to be.”

“Listen,” said Albee, leaning toward her. “You’ve got a wonderful set of characters with absolutely wonderful interrelationships with each other. And your ear is splendid … don’t you think her ear is wonderful? But when you add the goddess of the moon, I don’t believe it for a second! I think she thinks it would be nice if she were.”

“That’s true,” said Sherman, “but one of my ideas is that you have myths everywhere and then you have two people trying to be mythical, searching for some kind of transcendence. The point of the mythical reference is that it was going to fail and be unfulfilled …”

“How do you be mythical? Why do you bother us with [the myth]?” asks Albee. “Does it make your play better? Does it make it bigger in some way? I thought this was a play about a guy who has a problem with drugs and a girl who is bulimic. I believe the interaction between these two people—not as goddesses or mythical people. It’s an unnecessary imposition of the mythical; it gets in the way of reality. As a general rule, never do anything that allows the audience to move out of the reality and story of the play. You’ve got so much good stuff in there. Don’t burden it with stuff they don’t need.”

It is a lot for the young playwright to chew on. Days later, she is still processing.

“At first I was ready to change the characters’ names and all that,” said Sherman. “Then I talked to [Theater Department Chair] Roger Bechtel and we talked about how it wasn’t a gospel, it was one person’s opinion. I kept thinking ‘Wow, I should be upset, I should be floundering more.’ Then I realized that he wouldn’t take the time to make something better if he didn’t think there was something there that deserves to be bettered.

“As a writer, you’ve got to get criticized; it’s how you grow. Edward Albee read my play. He read it twice and had specific things to address about it. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, fantastic.”

Caitlin Hylan was similarly smitten. “Mr. Albee was incredibly articulate and sharp,” she said. “I was thrilled and fascinated. When will we ever, ever get that opportunity again in our lives? But I do think his concept of what kind of play deserves to be performed is very specific to the style that he writes in. He said a play that can’t be performed without two chairs and a lightbulb shouldn’t be performed and I don’t agree. I think there are many plays that can’t be performed that way that are very high quality.”

Agree or disagree, Albee’s participation with the students that day demonstrated the power of his ideas. The legendary playwright, the myth, was just a man after all. And all they needed to create something riveting was there: a circle of chairs, a lightbulb, a cast of characters, and a conflict of ideas.

All photos by Brian Wedge.